OCEAN NAVIGATOR NO. - JUNE 1990

Japanese challenges

A voyaging couple discovers the difficulties and rewards of voyaging in Japan

by: Marcia Reck

The time was 0600. Dave woke me for my watch and I stumbled up the companionway ladder into the cockpit of Mañana, our 35 foot Fuji cutter. Slowly my sleepy brain began to register that something was not as it should be. The world was gray. Accustomed as I now am to the tropics it took me a few seconds to come up with the appropriate word: “Fog.” It’s been nearly eight years since we last encountered this phenomenon off the Washington-Oregon coast. We were now en route from Guam to Okinawa Japan. Dave, tired and bleary-eyed, went below to sleep, leaving me to reacquaint myself with fog. I soon rememhered why I so dislike sailing— or motoring—in fog: The cold and damp sinks into my bones. Most of all, the fog was disquieting. I couldn’t see much more than half a mile in any direction.

Leaning against the dodger, eyes straining to catch the slightest hint of a darker shape in the grayness, I said a word of thanks to our Autohelm 800. This small unit steers Mañana with the help of our Aries wind vane. It was our first passage with an autopilot. Until this morning we had seen it as a wondrous convenience that freed us from long hours at the wheel while under power. In the fog, I saw the autopilot as a safety device as well, it allowed me to concentrate all my attention on navigation. instead of having to continually steer with my eyes glued to the compass. As I stood scanning fore, aft, and abeam, I slowly became aware of a sound just audible above the chugging of Mañana’s 25-horsepower Westerbeke engine. I searched the murk overhead, thinking I heard an airplane. Obviously, I was still not completely awake, nor fully returned to navigating in fog. Gradually it occurred to me that the sound was not constant, but coming at regular intervals. A foghorn! I could still see nothing but walls of gray mist. Wanting company—and another pair of eyes—I called Dave on deck. After we both fruitlessly scanned the murk for a minute or two, I decided to try the VHF radio. ‘Ship in the vicinity of x degrees, x minutes north; x degrees, x minutes east, this is the sailing vessel Mañana; how do you copy?” Silence; then I got an inspiration and I asked: “Ship sounding fog signal in the vicinity Much to our relief a pleasant Aussie voice replied. We felt even greater relief when he said that his ship had just emerged from the fog and that they had us on radar as well.

The fog began to lift shortly thereafter. Within an hour or two we had clear skies and good visibility.

In the four months we have since spent cruising Japan, we have not again encountered fog. Yet the fog was a fitting introduction to cruising in Japanese waters. It was the first in a long list of navigational tests that we’ve faced.

Unceasing traffic

About 36 hours after the fog lifted, we were hove to off the SE tip of Okinawa, waiting for daylight to enter the port of Naha. The U.S. Sailing Directions state in no uncertain terms that it is unwise to try to enter Naha at night. We had no desire to test the truth of that statement. Standing watch that night as we drifted, we had our first glimpse of the concentration of shipping that passes through Japanese waters. We never had fewer than five other vessels in sight. I doubt we’ve been underway since with less company. Container ships, tankers of every size and type, tugs, barges, ferries, and an incredible variety of fishing craft have crossed our bows. About the only sort of vessel we haven’t seen at sea is a sailboat, aside from other American voyaging boats with whom we’ve been sailing. The sport of sailing is still relatively new in Japan and racing is far more popular than voyaging. We’ve not yet seen a Japanese sailboat outside protected waters.

The following morning, approaching the entrance to Naha, we were glad we had heeded the warning in the Sailing Directions. Even in daylight it was confusing. Reefs were not easily distinguished and there were far more markers and buoys than our chart indicated.

While Japan’s buoyage system at first took us aback we have since found it to be excellent. Obstructions and harbor entrances are almost without exception very clearly marked. Lights work, a welcome change after years of dealing with the often poorly- maintained lights of the tropical Pacific islands. Most harbor buoys have the of the port clearly noted in both “kanji” (Japanese characters) and “ romanji” (roman lettering) , helpful if you’re unsure whether or not you’ve got the right spot.

While the number of vessels in Japanese waters pose a major challenge for the small boat navigator, an even greater test is offered by the nearly unbelievable variety and number of fish traps, fish aggregation devices, fish pens, pearl farms, shellfish rafts, traps, pots, and nets that abound here. Charts are dotted with the rather nebulous notation “fishing reef, pa.” (position approximate). Is it a natural reef? Man-made? What’s the depth? You’re on your own, We lump all these appurtenances under the general heading of “aggravation devices.” To the navigator, they are nothing else. In Japanese waters they are everywhere, in both open and restricted waters. Rare is the bay that does not contain a raft or pen. On the plus side, rare too is the hay or channel which is completely blocked by pens. We’ve never been kept out of a desired anchorage by fishing activity.

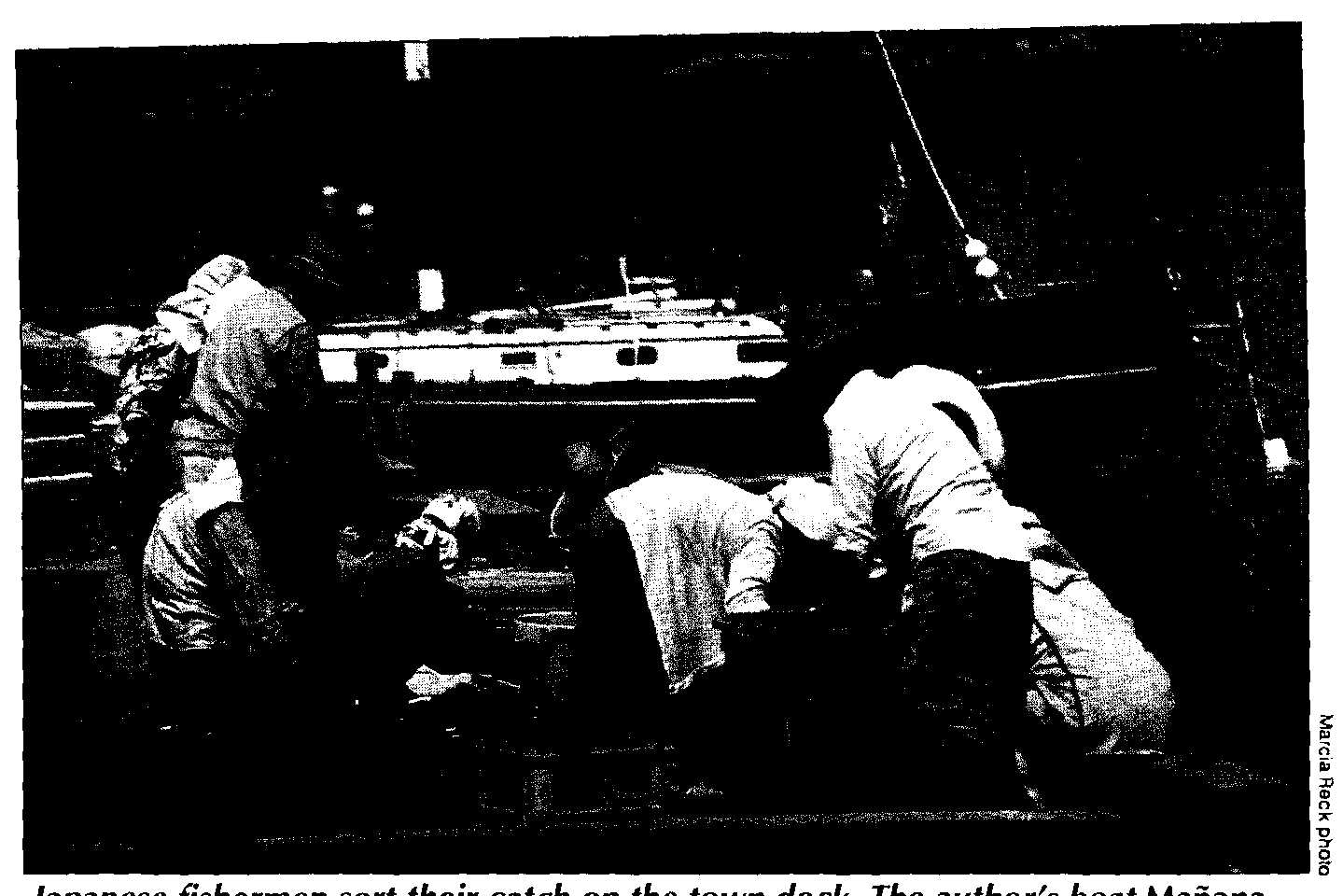

Japanese fishermen sort their catch on the town dock. The author’s boat Mañana can be seen in the background.

Just as these “devices” come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, they may he marked by just about anything. Some are lighted, some are not. One end of a net may be marked while the other is not. Markers may be flags, sticks, buoys, plastic jugs, or bits of styrofoam. Further confusion results from the fact that all these items may also be just flotsam and jetsam. A buoy may be attached to a net or trap or may just he floating free. By not actually running over anything that might be a marker, we avoided picking up anything in the propeller. Another hazard to propellers is provided by the large numbers of plastic bags in both harbor and coastal waters. The Japanese badly need to enact and enforce strong anti-littering laws. In the meantime, we hold our breath and cross our fingers while motoring across harbors or through tide lines.

Challenging currents

Possibly the greatest navigational challenge for the voyaging sailor is Japan’s tidal currents. While a small freighter may be slowed by a six-knot contrary current, it will still get through a channel in a reasonable amount of time. The vast majority of cruising sailboats will sit in one spot or even he pushed backwards. The only option is to wait for slack water. A favorable current may push you in the right directions, but you’ll still face the dangers of whirlpools and overfalls. It is wise to study charts, Sailing Directions, and tide and current tables closely. Use common sense as well. Given Japan’s tidal range of a minimum of six feet, if the flow of water is restricted there will he at least some tidal current.

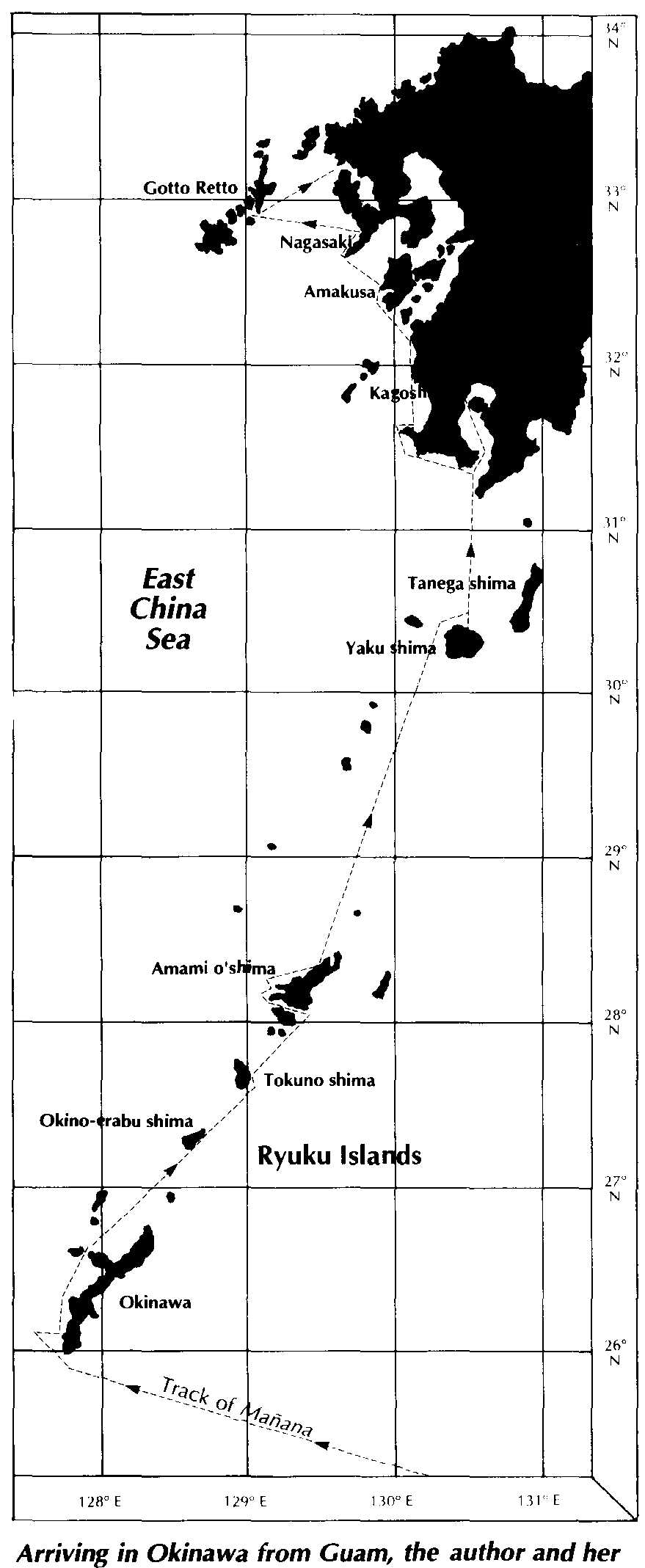

Arriving in Okinawa from Guam, the author and her husband sailed to Kyushu.

We failed the tidal current test the first time around. We were anchored in a protected bay in the Gotto Retto Island group, with a five-mile-long channel to pass through to reach open water. We had come through the channel to reach our anchorage, but we must have been lucky enough to enter near slack water. One of our charts of the group showed a current of three knots in the channel, while another showed no current. The latter chart showed five to six knots of current in a similarly configured channel a couple of miles away, so we should have noticed that something didn’t add up. Sure enough, ignoring both the tides and logic, we set out and ran right into a contrary four to five knot current. Pushing Mañana’s engine about as hard as we dared, it took us three hours to get through the channel. To add to the fun, a steady parade of vessels crisscrossed about us. Most nerve- wracking were the assorted barges and dredges involved in bridge construction in one of the narrowest parts of the channel.

We now carefully check the tides when planning passages. We’ve found that currents of five to ten knots are common in Japan’s Inland Sea, making careful plan- fling vital for the voyaging sailor in these waters.

In addition to tidal currents, major ocean currents also affect Japanese waters. In southern Japan, the greatest effect is felt from the Kuroshio Current. This current is an offshoot of the North Equatorial Current. It sets northeast along the west side of the Ryukyu Islands. The Kuroshio divides near Yakushima, the weaker branch flowing north through the Korea Strait. The stronger branch flows up the east coast of Kyushu then along the south coast of Shikoku. The weaker branch of the Kuroshio makes itself felt along the west coast of Kyushu by affecting tidal currents in the area. Enhanced by this ocean current, the north-setting flood currents are generally stronger than the southerly ebb currents. Voyaging among the Ryukyus, we never did feel the effect of the main branch of the current hut did encounter west-setting currents on several occasions. These must have been stray eddies of the Kuroshio as they seemed unaffected by the state of the tide. Between Yakushima and Kagoshima, at the south tip of Kyushu, we experienced a favorable NE current of about two knots.

“The U.S. Sailing Directions and charts have given us a never-ending stream of navigational tests.”

Incomplete directions

The U.S. Sailing Directions and charts have given us a never-ending stream of navigational tests. Dealing with natural harbors and bays, they are on the whole quite accurate. When it comes to man-made or improved harbors they are woefully behind the times. The Japanese government has been and still is on a frenzy of harbor building and upgrading. Rarely a day passed that we don’t see a dredge, concrete caissons, or a shipload of fill on the way to aid in the construction of yet another breakwater.

We’ve spent many an anxious moment off many a harbor entrance trying to reconcile the information given in the Sailing Directions with what we see with our own eyes. I read: “... is a small bay protected by a breakwater ;. . . A pier, 360-feet long is located on the east side opposite the breakwater Dave, at the helm, shakes his head. “No pier. There are two breakwaters, no; more than that.” I continue reading: “Except with winds between west and north, sheltered anchorage can he obtained by small vessels The wind is of course from the northwest, but we’re no longer sure whether that matters. The harbor certainly appears to offer complete protection.

American DMA (Defense Mapping Agency) charts are not much help either. Except for major ports, information is scanty. There are usually few depths given and breakwaters are rarely shown.

In such situations we inch forward under power, Dave steering and watching the depth sounder while I stand on the bow, peering into the usually murky waters. With so much boat traffic, we are generally able to spot a large fishing boat entering or leaving the harbor and can watch to see which way it goes. A wave and a yell and some sign language will get you a rough idea of the depths inside.

We now know that nearly every village has a harbor offering excellent protection from everything short of a typhoon. Japan’s fishing fleet is such an important part of the country’s economy that the government must provide for its protection. At least in Kyushu and the Ryukus, typhoon holes for small craft are rarely more than a long day’s sail away. This is fortunate, as this area generally experiences at least one or two typhoons each year.

One characteristic of Japanese waters is heavy commercial traffic, from container ships to coastal tankers to fishing vessels. Belowe, a Catalina 30, is overtaken by a ship off the Gotto Retto Islands.

While U.S. charts could stand — serious updating, Japanese charts are quite accurate. For voyaging sailors on a budget, the catch is that Japanese charts currently cost about $25 apiece.

It is cheaper and considerably more entertaining to take your U.S. charts over to a nearby fishing boat and ask the crew about your proposed next destination. Ask is perhaps the wrong word. Point, wave, and gesticulate wildly are more like it. But even with few words in common, harbor information is easily obtained. In addition, you’ll most likely be invited to visit the fisherman’s home port. You may also be invited to sample some of the local white lightning, which will quickly diminish your resolve to get underway the next morning!

Such genuine hospitality—the fisherman truly wants you to visit his village—is the reward for passing the navigational tests of Japan. The friendliness of the Japanese people to foreign visitors has to he experienced to he believed. There are few foreigners traveling here now and even fewer cruising. Japan is far off the milk runs of Pacific voyaging. There were about a dozen foreign yachts in Japan this last year and that was a record high.

In the small fishing villages we were greeted with complete amazement. We suspect that in several villages we might have been the first foreign visitors. Even in the cities, “gaijin” (foreigners) are not a common sight. Old men gawk and school girls giggle. We have been taken to restaurants, invited to homes for meals and taken sightseeing. When we ask directions ashore, someone often goes out of their way to cheerfully lead us where we want to go.

Before coming to Japan, I pictured a crowded country with few empty spaces. Instead, we have found countless quiet hays to retreat to after we’ve temporarily had enough of city life. We’ve found the cruising to he unsurpassed, with one qualifier. We’ve done precious little sailing. Summer in southern Japan is a time of little wind, so we’ve motored almost all the way north from Naha. That aside, the anchorages, the picturesque fishing villages, and above all, the friendly people have made Japan a highlight of our voyaging days.

Contributing editor Marcia Reck is continuing her seven-year exploration of the Pacfic aboard Mañana.